Letter from London

the spark of looking at art and the joy of long, dark walks in yuletide London

Shortly after we arrived in London, Daniel and I headed to the National Gallery’s Poets and Lovers - an intimate look at Vincent Van Gogh’s final years. It took perseverance to maneuver through the packed show and we found ourselves bobbing around tight clusters of people documenting their viewing experience through the third eye of a smartphone. Fortunately, the drawings attracted little attention and I had space to study the vitality of Van Gogh’s draftsmanship. With a few sure strokes of pen and pencil, Van Gogh could animate landscapes and the atmosphere around them. Despite Van Gogh’s escalating loneliness and mental deterioration, he never seemed to put a line wrong.

Do you remember Sherlock Holmes's famous quip to Dr. Watson? ”You see, but you do not observe.” I have been guilty of this particular shortcoming. Looking at art with care is a skill and a luxury. It takes time to take in detail, to take a break from routine, to move away from a device, to ponder the thousand details that flow into the execution of exceptional art. And it often takes solitude to do all of the above. Age also matters—as we evolve we look at paintings differently.

After Van Gogh, we meandered around the main galleries revisiting old favorites, and I was particularly drawn to portraits of children, most of whom were portrayed like minuscule adults with adult gestures. Or with cheeks so rouged they seemed feverish. Some of these portraits were finished posthumously which was, for me, especially heart-wrenching. I eventually wound up in front of Paul Delaroche’s portrait of Lady Jane Grey and remained there. Decades earlier I paused in the same spot during a class and was mocked by the tutor for my attraction to “theatrical sentiment.” Then he dismissed the painting as mawkish and populist.

He was wrong. It’s a fantastic painting with a famous story. To safeguard Protestant rule King Edward VI appointed his cousin Lady Jane Grey his successor after he died in 1553. She was the Queen of England for nine days until the winds shifted and she was imprisoned, then executed and replaced by her Catholic rival Mary Queen of Scots. I love everything about this composition. The somber, muscled executioner in symbolic dark red breeches who doesn’t relish the task at hand. The difference in scale between the executioner and Lady Jane is also arresting— like putting Liam Hemsworth adjacent to the Olsen twins. The devastated ladies-in-waiting with their long, exposed necks. The elderly nobleman gently guiding Lady Jane’s head to the executioner’s block. The straw waiting to absorb the gore. The bewildered, frightened Lady Jane and her sumptuous snow-white drapery.

For years I let a condescending tutor determine my taste and scurried past this canvas lest I appear sophomoric. But I think that was only part of it. I just wasn’t ready to observe, to connect the dots. Lady Jane was just seventeen, a year younger than our late daughter Bailey. They both had formidable intellects. Lady Jane was already a scholar, unusual for a woman of her day. Both were in the wrong place at the wrong time but had very different executioners. I think their similarities end there — I doubt Lady Jane had a pierced brow and a tattoo.

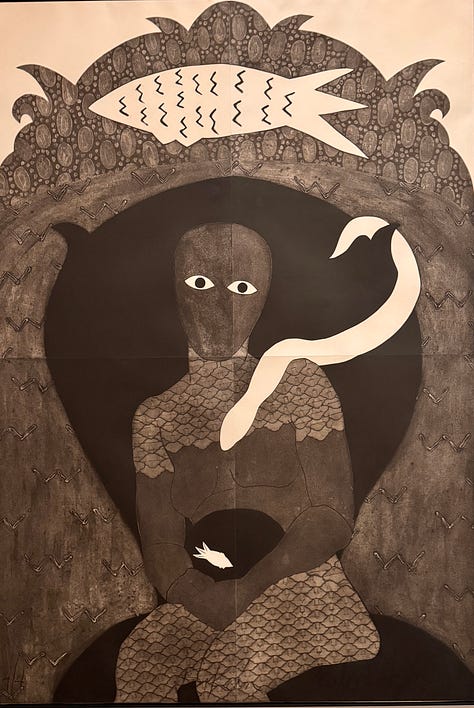

Initially, grief pushed me to seek beauty in the natural world, which is easy to find in my native Colorado. And I will always seek that. But having just spent day after day looking at art through this different, still-fresh prism of mourning, I also found solace in the timeless ancient and contemporary narratives embedded in fine art, architecture, and design. Our mortality is a given but our stories often remain. Great art is not only generous—it’s also dynamic because it offers us the potential for transference. When I feel this electricity, I stay inspired to keep painting and writing despite a world that seems constantly off-kilter.

As for my favorite city, Samuel Johnson put it best: “When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life.”

Thank you for this transference of adoration, love, critical thinking, and, as always, a wonderful kind of welcome into your very beautiful home; your home in the world, this necessary maternal viewpoint. As much as John Soane’s house is wildly unique, jam packed with questionably sourced antiquities and indulgent, I can’t help but feel that he knew we’d all come to London, to his house, looking for answers in those rooms. There lies a sense of raw human truth. Perhaps, John Soane’s was a bit of a slate sidewalk magician, a gin soaked soothsayer, a shaman of the city dwellers? 🌟

Isa, your words are always insightful and inspiring. I know we are both missing our daughters during this holiday season. As you once told me the club no one wants to belong to. It doesn't get easier, only different. Love to you and your dear family. Love, Jan